Share This

Related Posts

Tags

Net-Zero Design

By Erica Rascón on Sep 5, 2012 in News

Architectural design and build are art forms of a functional sort, the kind that balance creativity with budget constraints. Perhaps if budgets weren’t an issue, there’d be nothing but beautiful, environmentally-friendly buildings. More realistically, sustainable design for the earth must also be sustainable for the company’s bottom line.

Architectural design and build are art forms of a functional sort, the kind that balance creativity with budget constraints. Perhaps if budgets weren’t an issue, there’d be nothing but beautiful, environmentally-friendly buildings. More realistically, sustainable design for the earth must also be sustainable for the company’s bottom line.

According to Scientific American, homes and commercial buildings contribute to approximately 40 percent of the nation’s energy consumption, not to mention billions of dollars in energy costs for residential and commercial customers. By making more efficient buildings, the nation’s carbon footprint can reach new lows while saving consumers money. Pushing down development costs for such projects is the best way to achieve more widespread adoption of these techniques.

Net-zero energy designs are models of such efficiency. These buildings are like miniature factories, producing enough renewable energy to fuel the inhabitants’ operations without drawing from the grid. In fact, net-zero buildings can even create a surplus of energy that is sold to energy providers or exchanged for credits.

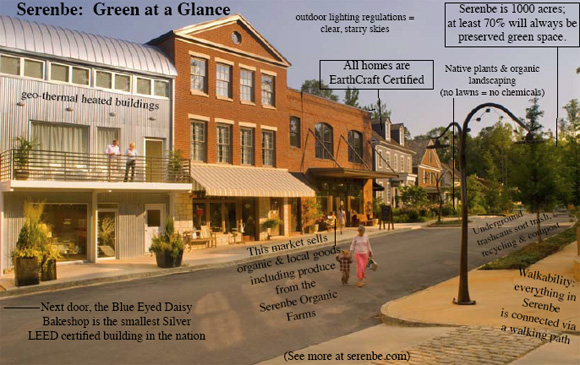

The concept has appealed to environmentally conscious designers and consumers throughout the nation. From 2005 to 2011, residential green building experienced an increase of 15 percent according to a McGraw-Hill Market survey. Communities such as Serenbe in north Georgia and Prairie Crossing of Illinois are among those that use sustainable building techniques, including LEED certification. They’ve also incorporated large amounts of preserved open space into their communities, and encourage residents to use alternative transportation. Builders KB Home, Shea Homes, and Nexus EnergyHomes jump started bi-coastal net-zero communities in eight states with notable success.

In the commercial sector, there are 21 certified net-zero commercial buildings across the nation and another dozen in the marking. Universities are also on board. UC Davis’ West Village has reined in the power of zero-waste designs, and boasts that it is the largest net zero energy community in the country. Energy efficiency was improved 50 percent over existing standards thanks to innovative building, and the remaining power needs will be supplied by renewable sources, like a biodigester that will recycle waste into energy.

While the population of net-zero buildings has grown markedly, it still represents a small fraction of new builds in the nation. Undoubtedly, these structures are capable of reducing carbon emissions and dependence on the grid. Indeed, occupants can bring their energy bills to zero, or better yet have the energy company paying them. So why hasn’t every design and build team across the nation jumped on the net-zero jet plane? The reasons are multifaceted but mainly circle back to the ever-present balance sheet.

Net zero properties can be a tough sell. The buildings are only as efficient as their occupants. A multitude of small decisions each day help the building operate optimally: turning off even energy efficient appliances when not in use; maintaining water and waste recycling systems; and being aware of resource consumption. Getting the most out of net-zero buildings requires a conscious shift in mental processes. Firms recognize that traditional designs require less on the part of potential buyers, increasing the buildings’ marketability.

Firms face a myriad of costly obstacles when building in different regions. In the Southeast, passive heating and envelope designs transform buildings into saunas. Advanced low-energy cooling systems increase costs in this region compared to other areas. Net-zero energy designs require spacious, flexible lots and ideally offer access to sunlight and cross breezes, all things that can be hard to come by in metropolitan areas. Firms with interest in energy efficient design must first overcome the challenge of keeping costs low, regardless of the location. Data from Inman News suggests that net-zero homes cost $30,000 to $40,000 to build, but those figures are on the rise along with construction costs as a whole.

Perhaps the weight isn’t as heavy as it first seems. Projects by MoSA reveal that solar energy has become more accessible, dropping nearly 50 percent in recent years. Net-zero buildings can use an average of 90 percent less energy to build and operate, saving cash for investors and occupants. Federal tax credits provide recompense of up to 30 percent on solar power systems. Tom Black, vice president of Eco Plus Group USA, calculates that many net-zero systems pay for themselves within six years.

A building that pays for itself certainly appears to be a worthwhile investment, particularly for homeowners who are building their own private residences. For commercial and institutional projects, however, the recuperated funds arrive too late. The ball and chain that we know as the bottom line still holds firms back, making the six year waiting period between investments and returns seem impassable.

What steps could be taken to close the gap between developer speculative net zero projects and achieving more attractive ROI?