By Erica Rascón on November 5, 2012 in News

Without making a few drastic changes to the way that American students see creativity, Americans will continue to lag behind other nations in innovative architecture.

As the daughter of a very zealous architect, I have grown up tuned-in to the trends that pass through the world of architecture. Our coffee table was stacked with photography books depicting the boldest, most ingenious designs. As a teen, though, I looked at those texts like images from another world. They differed from the boring block school that I attended or the quadrant-riddled hospital a block from my house. Those fancy buildings were elsewhere. Like Sweden.

Not much has changed since I was a teen and the rest of the world is beginning to take notice.

With the exception of a few shining stars (Skidmore, Owings & Merrill and Steven Holl come to mind in recent history) American architecture seems to lack the creative edge seen in places like Singapore, Japan, Denmark, and China. The lack of innovation goes beyond aesthetics into energy efficiency, resource harvesting and conservation. Many new American firms refuse to toe the boundaries already broken by international counterparts.

Some believe the cause is a lack of creativity on behalf of American clients and architects. An appreciation and pursuit of ingenuity has dwindled in our culture. Newsweek ran an article featuring the research of Kyung Hee Kim, associate professor of educational psychology at the College of William & Mary. Kim administered the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking (TTCT) which measures three fields of creativity, with questions including topics such as art, mathematics, engineering, science, and interpersonal relationships. After studying the results of 300,000 American participant, Kim noticed a marked decline in creativity when comparing notes to past studies. The scores for elaboration—“ the ability to develop and elaborate upon ideas and detailed and reflective thinking [that] also indicates motivation to be creative”—dropped most significantly “by 19.41% from 1984 to 1990, by 24.62% from 1984 to 1998, and by 36.80% from 1984 to 2008.” According to the tests, the nation has lost the motivation to be creative. As Kim sees it, “The recent decreases in creativity measures indicate a threat to national security.”

She stands corrected on a few fronts. In the past, American ingenuity propelled a young, inexperienced nation to stand as a world leader on the forefront of science, technology, and industry. Such haughty accolades seem to be slipping through our fingers by the day. Beyond walking with our heads held high, ingenuity leads to creative ways to solve daily problems. Without that creativity, our very cities are at risk.

Brent Ryan, the Linde Career Development Assistant Professor of Urban Design and Public Policy in MIT’s Department of Urban Studies and Planning believes that “bolder, more distinctive civic projects can enhance the comparative advantages of cities as dense, diverse, lively places to live.” In a recent interview he explained that shrinking cities such as Detroit and Philadelphia need a boost in inventiveness to get back on track. Good design (not nearly functional design) shows residents that a city is moving forward; without visual representations of progressive thinking, “it’s harder for [residents] to see a development in their city that leads the way forward.” Good design speaks to structures that inspire minds and solve problems: managing stormwater, recycling graywater, conserving and producing energy, and so fourth. Dying cities need buildings that cooperate with the surrounding environment and support healthy lifestyles for dwellers’ instead of working against them both. To Ryan, innovation should extend beyond opera houses and high rises to “reunite a social agenda with a progressive design agenda.” Without such a creative approach to building, struggling cities risk falling into further disarray.

Harboring a tradition of mediocre design may also threaten our nation by alienating the creative minds that we have with us. Frank X. Arvan, President of the American Institute of Architects in Detroit, issued a compelling letter beseeching the community to re-evaluate the “lack of creative and exciting commissions for local architects.” Arvan notes that without cooperation between local clients and local architects “we create an architectural ghetto that promotes mediocrity.” The result is “brain drain,” the departure of creative minds from an area where they cannot work to areas where they seem to flourish (in this case, abroad). A nation’s reluctance to embrace and promote forward-thinking design potentially results in a creative exodus, leaving a void in our nation that we simply cannot afford to fill.

A lack of creativity proves to be a threat to American security, indeed. When reflecting on her research, Kim noted that creative development begins in our formative years. To defeat its decline, we must re-evaluate the way that creativity is approached in the classroom, from pre-K to university level studies. Promoting innovative problem solving, inventiveness, and simply restoring our will to create are necessary to our nation’s survival.

Unfortunately, the dynamics of creativity are difficult to measure quantitatively, meaning that they will go unnoticed on standardized test. Under the current policies, what can’t be measured on standardized tests will go ignored. Improving the future of architecture and similar creative fields requires a second look at the way that our schools asses student and teacher success. Our security as a nation depends on it.

What efforts have you observed to burgeon creativity in the classroom and the community?

- Orange Cube – Jakob Macfarlane Architects, Lyon France

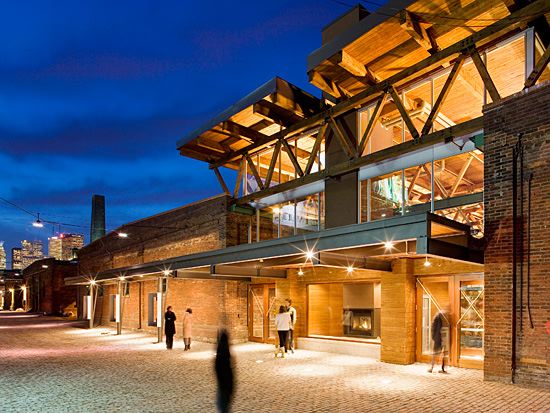

- Young Centre – Kuwabara Payne McKenna Blumberg Architects, Toronto

- Glaxo Smith Kline – from Coarchitecture in Quebec, CA

- Interior of Glaxo Smith Kline Admin building – Quebec By Coarchitecture

- The Metropol Parasol in Seville, Spain by Juergen Mayer

- Seed Cathedral/UK Pavillion was temporary exhibit for the World Expo in Shanghai. Conceived by architect Thomas Heatherwick

- This Puma building in Boston, MA is made of shipping containers by Lot-Ek