Share This

Related Posts

Tags

Next Gen Design

By Erica Rascón on Sep 18, 2013 in News

Commercial developers are seeking fresh new insights—and in some cases, designs—from the next generation of creative thinkers: students. Developers of small towns and established institutions are looking past architects and into the untested waters of university classrooms. Student-inspired development has become more common throughout the nation, with good reason.

To many observers, American architecture had become stale, lacking the creativity seen in other leading nations. The high costs did not yield the cutting edge buildings developers yearned for. In response, educators across the US shifted their focus, intensifying emphasis on innovation and good, old-fashioned out-of-the-box thinking. As an indirect result, universities soon became the place to seek fresh insight at a very affordable price point.

Youth has become a unique asset. Creativity flows unhindered by status quo or past disappointments. This generation has also been shaped by rapidly-changing technologies, boundless research opportunities, and an atmosphere  that promotes sustainability and resourcefulness. Students have become the ideal inspiration for those who are looking to develop their business, institution, or city on a budget while tapping into the mindset of the future.

that promotes sustainability and resourcefulness. Students have become the ideal inspiration for those who are looking to develop their business, institution, or city on a budget while tapping into the mindset of the future.

Montana State University architecture students joined forces to help Big Horn County Historical Museum and Visitors Center recreate its image. Students created displays for the museum, designed a new logo, created murals, and organized a cross-referencing system that would make navigating the ground’s nearly 30 historic buildings more manageable.

“The students inspired us to do so many things,” says Diana Scheidt, museum director. Interest in the museum has spiked, particularly due to the students’ model replica of Fort Custer which disappeared nearly a century ago. The young adults brought it back via plenty of research and a nifty 3D printer.

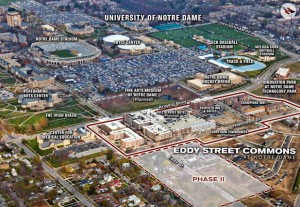

School of Architecture students at the University of Notre Dame were called upon to help with future development plans for South Bend (left). South Bend leaders become interested in capitalizing on the group, hoping to reinvent the area as a retail and dining destination for students and visitors alike.

To complete the project, the student team studied 11 successful college towns in the US before presenting ideas to community officials and residents. Proposals included the addition of mixed-used facilities with budget-friendly housing, more shops and cafes, and expanded roadways to promote pedestrian traffic and cycling. These projects would help link the isolated university to the nearby town, encouraging economic and social opportunities to flow in both directions. Jitin Kain, director of planning for South Bend, has announced that developments in the downtown area are already in progress.

W hile university students can offer unique insights, the cost effectiveness of their services undoubtedly plays a role in their value. Student projects save cash. Tweaking an amateur project may prove to be more economically savvy than purchasing a design from an established firm.

hile university students can offer unique insights, the cost effectiveness of their services undoubtedly plays a role in their value. Student projects save cash. Tweaking an amateur project may prove to be more economically savvy than purchasing a design from an established firm.

Mayor and trained architect Gavin Harris sought the help of students to create development and expansion plans for the town of Ruthin (right), located in North Wales. His decision was made two fold. Primarily, students are the visionaries of the future and he wanted to ensure that his town would appeal to future artisans and tourists. Secondly, student designs fit the town’s modest budget.

“If we had not done it this way, we would never have been able to afford it. A private practice would charge £40,000-£50,000,” he said in an interview with BBC News. The student-led initiative cost less than £5,000.

Urban SOS, a student competition sponsored by AECOM and hosted by American Institute of Architects NY, tackled resident issues this year. With the intent of vanquishing the slums, finalist teams focused on a suburb of Ciudad Juarez, the Kiberia neighborhood of Nairobi, and inner Bogotá. The Kiberia team won, taking home $5,000 as a grand prize. They were also awarded $25,000 toward making the project a reality. The neglected neighborhood certainly did not have the funds to propel its own renaissance. Through student award money and free project planning, a new beginning is now within reach.

The recession may have sparked leaders’ initial interest in student designs but the amateur projects are not likely to be abandoned as the economy recovers. Their value has been firmly demonstrated. Perhaps now, larger cities and companies will also latch onto the trend, creating an interesting dynamic between budding professionals and their established counterparts.

Know of a project in your city that involved student participation in the planning effort? Tell us about it.