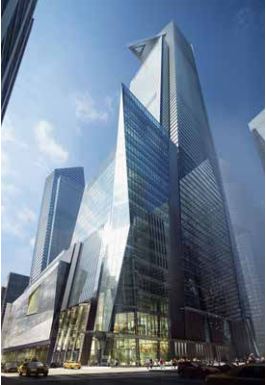

3D Printed Apartments

A reality in China

Gutenberg invented the printing press in 1439; since then the printing industry has evolved, from printing blocks to 2D printers with the capacity of mass-producing documents in just minutes. Today, 3D printers are capable of creating pretty much anything, from mechanical parts to prosthetics to buildings. Even though it’s been 32 years since an engineer […]